Chester James Carville Jr. (born October 25, 1944) is an American

political consultant

Political consulting is a form of consulting that consists primarily of advising and assisting political campaigns. Although the most important role of political consultants is arguably the development and production of mass media (largely tel ...

, author, and occasional actor who has strategized for candidates for public office in the United States and in at least 23 nations abroad. A

Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

, he is an expert

pundit in

U.S. elections who appears frequently on

cable news

Cable news channels are television networks devoted to television news broadcasts, with the name deriving from the proliferation of such networks during the 1980s with the advent of cable television.

In the United States, the first nationwide ca ...

programs, podcasts, and public speeches.

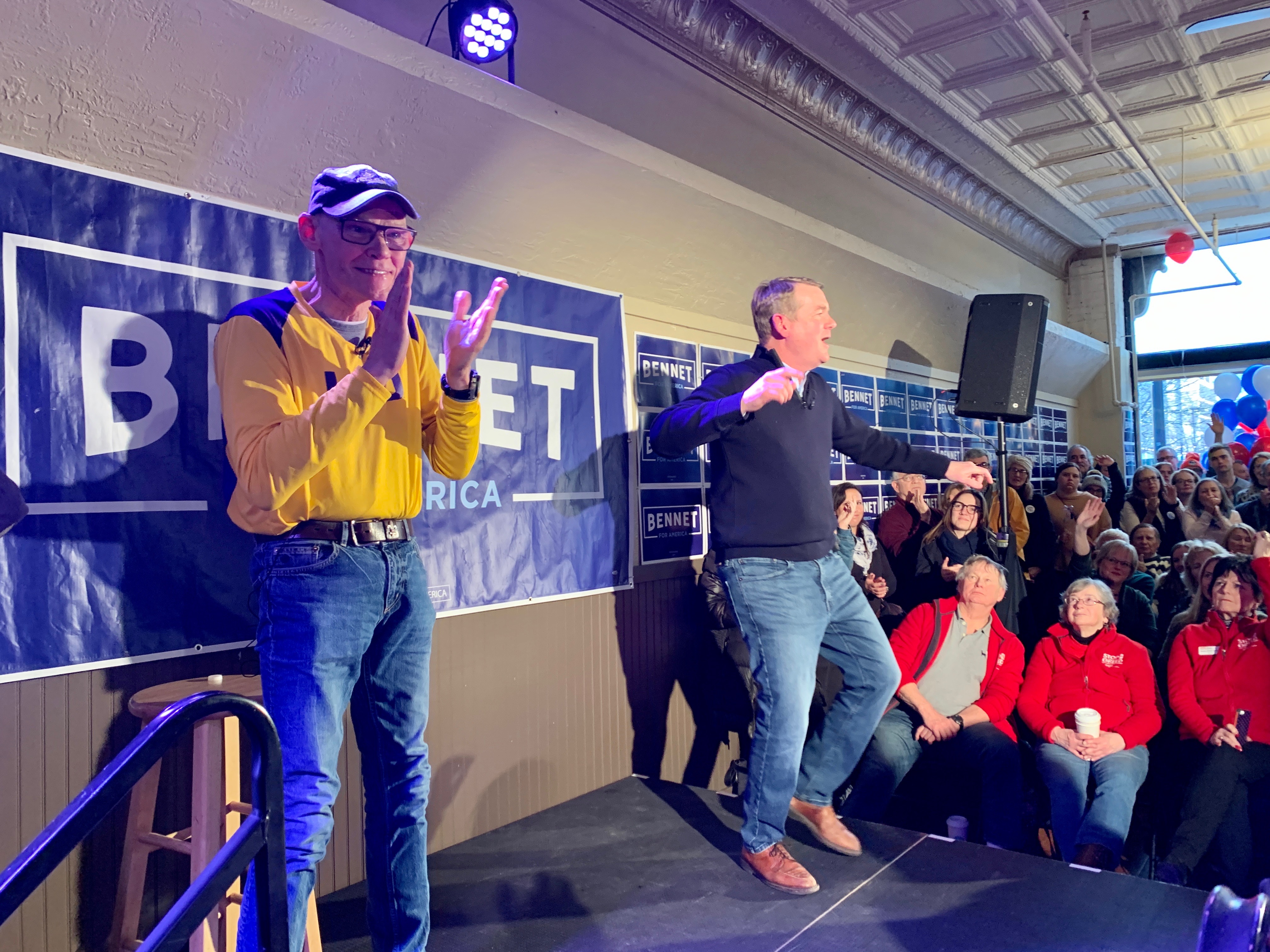

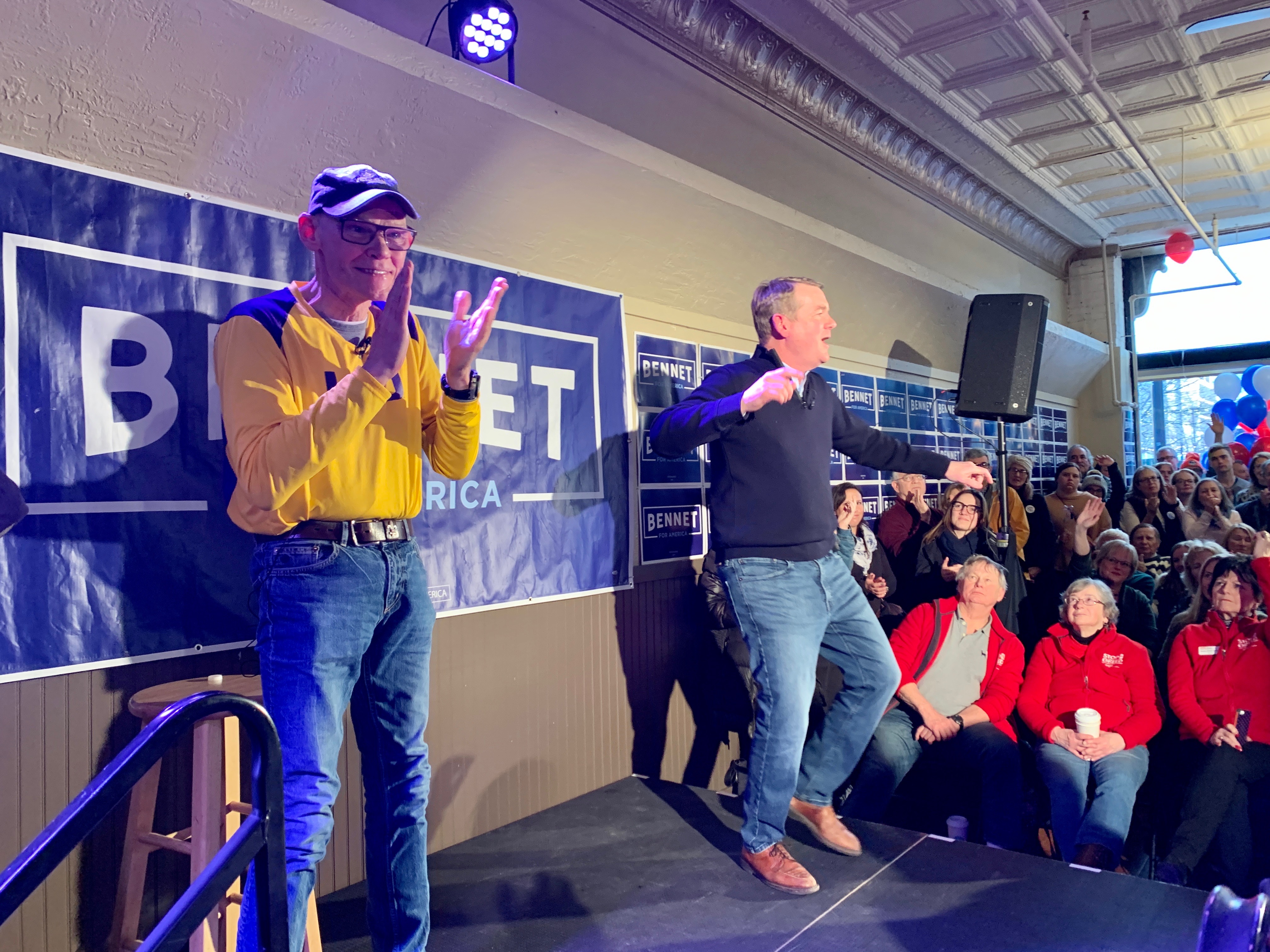

Nicknamed the "Ragin' Cajun", Carville gained national attention for his work as a lead strategist in

Bill Clinton's winning 1992 Presidential campaign. Carville also had a principal role crafting strategy for three unsuccessful Democratic Party presidential contenders, including Massachusetts Senator

John Kerry in 2004, New York Senator

Hillary Clinton in 2008, and Colorado Senator

Michael Bennet's campaign for the Democratic Party presidential nomination in 2020.

Early life and education

Carville was born on October 25, 1944, at a U.S. Army hospital at

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

's

Fort Benning

Fort Benning is a United States Army post near Columbus, Georgia, adjacent to the Alabama–Georgia border. Fort Benning supports more than 120,000 active-duty military, family members, reserve component soldiers, retirees and civilian employees ...

, where his father was stationed during World War II. His mother, Lucille (

née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

Normand), stayed behind in

Carville, Louisiana

Carville is a neighborhood of St. Gabriel in Iberville Parish in South Louisiana, located sixteen miles south of the capital city of Baton Rouge on the Mississippi River. Carville was the childhood hometown of political consultant James Carville, ...

, where James was raised, but went to Ft. Benning long enough to have her firstborn son. Carville would later note: "We were availing ourselves to free government health services." Lucille Carville, a former school teacher, spoke French at home, and sold the ''

World Book Encyclopedia

The ''World Book Encyclopedia'' is an American encyclopedia. The encyclopedia is designed to cover major areas of knowledge uniformly, but it shows particular strength in scientific, technical, historical and medical subjects. ''World Book'' wa ...

'' door-to-door, and his father, Chester James Carville Sr., was a

postmaster as well as owner of a

general store.

Carville, Louisiana, a neighborhood in the city of

St. Gabriel, in

Iberville Parish

Iberville Parish (french: Paroisse d'Iberville) is a List of parishes in Louisiana, parish located south of Baton Rouge in the U.S. state of Louisiana, formed in 1807. The parish seat is Plaquemine, Louisiana, Plaquemine. At the 2010 U.S. census, ...

, located sixteen miles south of the capital city of

Baton Rouge on the

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, was named after his paternal grandfather, Louis Arthur Carville, who was once the postmaster. Louis Arthur's mother, Octavia Dehon, was of

Belgian

Belgian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to, Belgium

* Belgians, people from Belgium or of Belgian descent

* Languages of Belgium, languages spoken in Belgium, such as Dutch, French, and German

*Ancient Belgian language, an extinct languag ...

parentage and had married John Madison Carville, described in a biography as "

Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

-born" and a "

carpetbagger," both of whom established the general store operated by the family in Carville, in 1882. Carville has seven siblings (Bonnie, Mary Ann, Gail, Pat, Steve, Bill, and Angela.).

Among Carville's earliest political campaign work was ripping down the campaign signs of a candidate for public office during his high school years. Carville graduated from

Ascension Catholic High School

Ascension Catholic High School is a private, Roman Catholic high school in Donaldsonville, Louisiana. It is the oldest Catholic school in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Baton Rouge

History

Ascension Catholic was established in 1845 as St. Vincent ...

in

Donaldsonville,

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, in 1962.

He attended

Louisiana State University

Louisiana State University (officially Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, commonly referred to as LSU) is a public land-grant research university in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The university was founded in 1860 nea ...

(LSU) from 1962 to 1966, but did not graduate at that time. In a 1994 feature in ''

Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print magazine in 1933, it was widely ...

'', Carville characterized himself as "something less than an attentive scholar. I had fifty-six hours' worth of Fs before LSU finally threw me out."

Carville served a two year enlistment in the

United States Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through combi ...

, from 1966 to 1968, where he was stationed stateside, at

Camp Pendleton

Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton is the major West Coast base of the United States Marine Corps and is one of the largest Marine Corps bases in the United States. It is on the Southern California coast in San Diego County and is bordered by O ...

in

San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the List of United States cities by population, eigh ...

.

He achieved the rank of

Corporal

Corporal is a military rank in use in some form by many militaries and by some police forces or other uniformed organizations. The word is derived from the medieval Italian phrase ("head of a body"). The rank is usually the lowest ranking non ...

.

Following the conclusion of his military enlistment, Carville finished his studies at

LSU

Louisiana State University (officially Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, commonly referred to as LSU) is a public land-grant research university in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The university was founded in 1860 near ...

at night, where he earned his

Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University of ...

degree in General Studies in 1970 and his

Juris Doctor

The Juris Doctor (J.D. or JD), also known as Doctor of Jurisprudence (J.D., JD, D.Jur., or DJur), is a graduate-entry professional degree in law

and one of several Doctor of Law degrees. The J.D. is the standard degree obtained to practice law ...

degree in 1973. Carville is a member of the

Sigma Nu fraternity. He later worked as a junior high school science teacher. Before entering politics, Carville worked as an attorney at McKernnan, Beychok, Screen and Pierson, a

Baton Rouge law firm, from 1973 to 1979.

Political consulting in the United States 1970s to 1990s

Carville was trained in consulting by

Gus Weill

Gus Weill, Sr. (March 12, 1933 – April 13, 2018), was an American author, public relations specialist, and political consultant originally from Lafayette, Louisiana, Lafayette, Louisiana.

Background

Weill graduated in 1955 from Louisiana Sta ...

, who in 1958 had opened the first advertising firm that specialized in political campaigns in the state capital in Baton Rouge.

East Baton Rouge Parish, 1970s and 1980s

In a 2012 piece he wrote for

Foreign Affairs, Carville described one of his earliest political jobs distributing 'hate sheets' with negative literature on a political opponent at grocery stores on behalf of Ossie Bluege Brown, during Brown's 1972 campaign for district attorney of

East Baton Rouge Parish

East Baton Rouge Parish (french: Paroisse de Bâton Rouge Est) is the most populous parish in the U.S. state of Louisiana. At the 2010 U.S. census, its population was 440,171, and 456,781 at the 2020 census. The parish seat is Baton Rouge, ...

. Two years earlier, Brown had

defended Staff Sergeant David Mitchell, the first of 17 soldiers charged in connection with the deaths of villagers during the

Mỹ Lai massacre

The Mỹ Lai massacre (; vi, Thảm sát Mỹ Lai ) was the mass murder of unarmed South Vietnamese civilians by United States troops in Sơn Tịnh District, South Vietnam, on 16 March 1968 during the Vietnam War. Between 347 and 504 unarme ...

. Brown's tenure as D.A. was marked by his crusades against narcotics and pornography. In 1973, Brown prevented Baton Rouge theaters from showing

Bernardo Bertolucci's X-rated film, ''

Last Tango in Paris

''Last Tango in Paris'' ( it, Ultimo tango a Parigi; french: Le Dernier Tango à Paris) is a 1972 erotic drama film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci. The film stars Marlon Brando, Maria Schneider and Jean-Pierre Léaud, and portrays a recently wi ...

,'' In 1979, Brown blocked the showing of the comedy, ''

Monty Python's Life of Brian

''Monty Python's Life of Brian'' (also known as ''Life of Brian'') is a 1979 British comedy film starring and written by the comedy group Monty Python (Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Terry Jones and Michael Palin). It ...

.'' Brown asked Baton Rouge magazine distributors not to offer the March 1977 issue of

Hustler

Hustler or hustlers may also refer to:

Professions

* Hustler, an American slang word, e.g., for a:

** Con man, a practitioner of confidence tricks

** Drug dealer, seller of illegal drugs

** Male prostitute

** Pimp

** Business man, more gener ...

, which a state court judge in Ohio ruled obscene.

In addition to his work as an attorney, in the late 1970s, Carville also worked for

Gus Weill

Gus Weill, Sr. (March 12, 1933 – April 13, 2018), was an American author, public relations specialist, and political consultant originally from Lafayette, Louisiana, Lafayette, Louisiana.

Background

Weill graduated in 1955 from Louisiana Sta ...

&

Ray Strother's Weill-Strother, a Baton-Rouge-based political consulting firm that, over the years, had assisted with electoral campaigns and political messaging for Louisiana governors

Jimmie Davis,

John McKeithen

John Julian McKeithen (May 28, 1918 – June 4, 1999) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 49th governor of Louisiana from 1964 to 1972.

Early life

McKeithen was born in Grayson, Louisiana on May 28, 1918. His father was a ...

,

Edwin Edwards, and U.S. Representative

Otto Passman

Otto Ernest Passman (June 27, 1900 – August 13, 1988) was an American politician who served in the United States House of Representatives for Louisiana's 5th congressional district from 1947 until 1977. As a congressman, Passman chaired the Hous ...

.

In the early 1980s, Carville served as executive assistant to

East Baton Rouge Parish

East Baton Rouge Parish (french: Paroisse de Bâton Rouge Est) is the most populous parish in the U.S. state of Louisiana. At the 2010 U.S. census, its population was 440,171, and 456,781 at the 2020 census. The parish seat is Baton Rouge, ...

mayor-president

Pat Screen

James Patrick Screen Jr., known as Pat Screen (May 13, 1943 – September 12, 1994), was an athlete, attorney, and politician from New Orleans. He was elected in 1980 as the Democratic Mayor-President of East Baton Rouge Parish from 1981 to 198 ...

.

In early 1985, Carville consulted to help

Cathy Long win a special election to central Louisiana's now defunct 8th congressional district, following the death of her husband,

Gillis William Long

Gillis William Long (May 4, 1923 – January 20, 1985) was an American politician and lawyer who served as a U.S. representative from Louisiana. He was a member of the Long family and was the nephew of former governors Huey Long and Earl Long ...

, of Louisiana's

Long family

The Long family is a family of politicians from the United States. Many have characterized it as a political dynasty. After Huey Long's 1935 assassination, a family dynasty emerged: his brother Earl was elected lieutenant-governor in 1936, and gov ...

political dynasty.

Texas senate race, 1984

In 1984, Carville became acquainted with his consulting partner

Paul Begala

Paul Edward Begala (born May 12, 1961) is an American political consultant and political commentator, best known as the former advisor to President Bill Clinton.

Begala was a chief strategist for the 1992 Clinton–Gore campaign, which carried ...

when Carville managed then Texas state legislator

Lloyd Doggett's unsuccessful campaign for

the open Texas Senate seat. Carville helped Doggett, an unabashed liberal and committed enemy of special interests, secure the Democratic nomination in a primary that included conservative U.S. Representative

Kent Hance

Kent Ronald Hance (born November 14, 1942) is an American politician and lawyer who is the former Chancellor of the Texas Tech University System. In his role, he oversaw Texas Tech University, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center and Ang ...

, and centrist former congressman

Bob Krueger

Robert Charles Krueger (September 19, 1935 – April 30, 2022) was an American diplomat, politician, and U.S. Representative and U.S. Senator from Texas, a U.S. Ambassador, and a member of the Democratic Party. , he was the last Democrat t ...

. During the primary, Carville borrowed a rubber vertebrae exhibit from a friend who was a personal injury attorney, and coached Doggett on using it as a prop on the stump to attack Krueger as a political

flip flopper who lacked resolve and 'backbone.'

During the general election, Doggett's opponent,

Phil Gramm

William Philip Gramm (born July 8, 1942) is an American economist and politician who represented Texas in both chambers of Congress. Though he began his political career as a Democrat, Gramm switched to the Republican Party in 1983. Gramm was ...

, leveraged vicious

identity-based attacks on Doggett. On one occasion, Doggett ended up returning small dollar fundraising he received from a gay rights group. Gramm emphasized themes of "family values," including his insistence at a June 1984 prayer breakfast on "having people who believe in Christianity in charge of government," and Carville counter-punched that theme as

anti-semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

. Doggett was defeated in the general election, polling 2,207,557 votes (41.5 percent), to Gramm's 3,116,348 votes (58.5 percent).

Finding himself out of work after the November 1984 defeat, Carville recalled, "I was scared to death, I was 40 years old, and didn't have any health insurance, I didn't have any money, I was mortified."

Pennsylvania gubernatorial election, 1986

During the 1986 general election, Carville helped

Bob Casey Sr.

Robert Patrick Casey Sr. (January 9, 1932 – May 30, 2000) was an American lawyer and politician from Pennsylvania who served as the 42nd Governor of Pennsylvania from 1987 to 1995. He served as a member of the Pennsylvania Senate for the ...

win election as the

42nd Governor of Pennsylvania by defeating his Democratic primary opponent,

Ed Rendell

Edward Gene Rendell (; born January 5, 1944) is an American lawyer, prosecutor, politician, and author. He served as the 45th Governor of Pennsylvania from 2003 to 2011, as chair of the national Democratic Party, and as the 96th Mayor of Philade ...

, in early 1986, and general election opponent

Dick Thornburgh's lieutenant governor,

Bill Scranton, who had taken the lead in the polls after announcing that his campaign was pulling all negative ads, and challenged Casey to do the same. However, the Scranton campaign misstepped by sending a mailer to 600,000 Republican voters that featured a letter from

Scranton's father. An additional brochure harshly attacking Casey's ethics was also included. Carville began counterpunching; he contacted journalists and characterized the mailer as outrageous. Scranton claimed that he did not know about the mailing, so Carville ordered 600,000 blank envelopes, loaded them up on a truck – mountains of envelopes – and dumped them on a street corner near Scranton's campaign headquarters. Television cameras captured the campaign, asking: "How could you send out this many envelopes and not know about it?" Three weeks before the election, a poster appeared statewide, depicting Scranton as a "long-haired, dope smoking hippie."

The race was virtually tied until five days before the election, when Carville launched the "guru," a

TV commercial

A television advertisement (also called a television commercial, TV commercial, commercial, spot, television spot, TV spot, advert, television advert, TV advert, television ad, TV ad or simply an ad) is a span of television programming produce ...

that portrayed Scranton as having been a regular drug user during the 1960s, also mocking Scranton's interest in

transcendental meditation

Transcendental Meditation (TM) is a form of silent mantra meditation advocated by the Transcendental Meditation movement. Maharishi Mahesh Yogi created the technique in India in the mid-1950s. Advocates of TM claim that the technique promotes a ...

and his ties to

.

The image of Scranton as a meditating, long haired, dope-smoking

hippie

A hippie, also spelled hippy, especially in British English, is someone associated with the counterculture of the 1960s, originally a youth movement that began in the United States during the mid-1960s and spread to different countries around ...

, with a background of

sitar

The sitar ( or ; ) is a plucked stringed instrument, originating from the Indian subcontinent, used in Hindustani classical music. The instrument was invented in medieval India, flourished in the 18th century, and arrived at its present form in ...

music, was credited with tipping the scales against Scranton in the

socially conservative

Social conservatism is a political philosophy and variety of conservatism which places emphasis on traditional power structures over social pluralism. Social conservatives organize in favor of duty, traditional values and social institution ...

rural sections of Pennsylvania where Carville selectively decided to run the "guru" TV commercial.

Casey went on to win the election by a narrow margin of 79,216 out of 3.3 million total votes cast.

Kentucky gubernatorial contest, 1987

In 1987, Carville worked as a campaign manager to cast Kentucky businessman

Wallace Wilkinson as a self-made millionaire

anti-establishment

An anti-establishment view or belief is one which stands in opposition to the conventional social, political, and economic principles of a society. The term was first used in the modern sense in 1958, by the British magazine ''New Statesman'' ...

gubernatorial candidate. Wilkinson, who had made his fortune in retail, and real estate development, and who was sued for not paying overtime to his employees, and refused to release his tax returns to the public, charged his Democratic primary opponents with wanting to raise taxes, and continually campaigned on creating a

state lottery

In the United States, lotteries are run by 48 jurisdictions: 45 states plus the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Lotteries are subject to the laws of and operated independently by each jurisdiction, and there is no ...

to raise public revenue. During the general election portion of the campaign, on September 25th, 1987, Carville appeared on

WLEX-TV's 'Your Government' public affairs program, and implored reporters to look into the background of Wilkinson's opponent

John Harper's family, noting: "there might be problems with some of Harper's children." After the incident, Harper confirmed that his son had been shot and killed by

Franklin County, Ohio

Franklin County is a county in the U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 census, the population was 1,323,807, making it the most populous county in Ohio. Most of its land area is taken up by its county seat, Columbus, the state capital and most ...

police during a 1978 pharmacy robbery. Wilkinson won

the general election polling 504,674 votes (64.5%) to Harper's 273,141 (34.91%), and as Kentucky's 57th governor, secured passage of a state constitutional amendment to allow a lottery.

Georgia gubernatorial contest, 1990

In 1989 and 1990, Carville assisted

conservative Democrat and four term lieutenant governor

Zell Miller

Zell Bryan Miller (February 24, 1932 – March 23, 2018) was an American author and politician from the state of Georgia. A Democrat, Miller served as lieutenant governor from 1975 to 1991, 79th Governor of Georgia from 1991 to 1999, and as U. ...

in winning the

state party's gubernatorial nomination in a five candidate contest that included

Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

Mayor

Andrew Young

Andrew Jackson Young Jr. (born March 12, 1932) is an American politician, diplomat, and activist. Beginning his career as a pastor, Young was an early leader in the civil rights movement, serving as executive director of the Southern Christian L ...

, then-state senator

Roy Barnes

Roy Eugene Barnes (born March 11, 1948)Cook, James F. (2005). ''The Governors of Georgia, 1754-2004, 3rd Edition, Revised and Expanded.'' Macon, GA: Mercer University Press. is an American attorney and politician who served as the 80th Govern ...

, and former governor

Lester Maddox

Lester Garfield Maddox Sr. (September 30, 1915 – June 25, 2003) was an American politician who served as the 75th governor of the U.S. state of Georgia from 1967 to 1971. A populist Democrat, Maddox came to prominence as a staunch segregationis ...

.

Miller campaigned on a platform of

shock incarceration boot camps for first time drug offenders, blasted Young for "an explosion of crime" in Atlanta, and painted Young with wanting to "run away from" the issue of drugs. At Carville's counseling, Miller made a state lottery in lieu of state tax increases a central theme of his campaign. Carville attributed Miller's eleven point primary victory over Young to the attraction of the lottery issue and its capacity to turn out white suburban voters. "Zell Miller was able to set the agenda, and the agenda was the lottery," Carville noted at the time.

Miller won the nominating contest in the August, 1990 runoff against Young, and later defeated

Johnny Isakson

John Hardy Isakson (December 28, 1944 – December 19, 2021) was an American businessman and politician who served as a United States senator from Georgia from 2005 to 2019 as a member of the Republican Party. He represented in the United State ...

in the November, 1990 general election. Miller was later a

keynote speaker

A keynote in public speaking is a talk that establishes a main underlying theme. In corporate or commercial settings, greater importance is attached to the delivery of a keynote speech or keynote address. The keynote establishes the framework f ...

at the

1992 Democratic National Convention and

2004 Republican National Convention

The 2004 Republican National Convention took place from August 30 to September 2, 2004 at Madison Square Garden in New York City, New York. The convention is one of a series of historic quadrennial meetings at which the Republican candidates fo ...

s.

Texas gubernatorial election, 1990

Carville consulted in 1990 for former Texas Congressman and sitting

state Attorney General

The state attorney general in each of the 50 U.S. states, of the federal district, or of any of the territories is the chief legal advisor to the state government and the state's chief law enforcement officer. In some states, the attorney gener ...

Jim Mattox

James Albon Mattox (August 29, 1943 – November 20, 2008) was an American lawyer and politician who served three terms in the United States House of Representatives and two four-year terms as state attorney general, but lost high-profile race ...

, a bare-knuckled political brawler who routinely traveled to

Huntsville

Huntsville is a city in Madison County, Limestone County, and Morgan County, Alabama, United States. It is the county seat of Madison County. Located in the Appalachian region of northern Alabama, Huntsville is the most populous city in th ...

to attend

state executions in Texas, the most active state in carrying out

the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

. On advice from Carville, Mattox who was seeking the Democratic gubernatorial nomination that year, based his campaign on the claim that a

state lottery

In the United States, lotteries are run by 48 jurisdictions: 45 states plus the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Lotteries are subject to the laws of and operated independently by each jurisdiction, and there is no ...

would solve Texas' revenue needs without additional state taxes.

With no facts to support the charge, Mattox also ran a television advertisement accusing his primary opponent, State Treasurer

Ann Richards

Dorothy Ann Richards (née Willis; September 1, 1933 – September 13, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 45th governor of Texas from 1991 to 1995. A Democrat, she first came to national attention as the Texas State Treasurer, w ...

a recovering alcoholic, as a

cannabis

''Cannabis'' () is a genus of flowering plants in the family Cannabaceae. The number of species within the genus is disputed. Three species may be recognized: ''Cannabis sativa'', '' C. indica'', and '' C. ruderalis''. Alternatively ...

and

cocaine

Cocaine (from , from , ultimately from Quechuan languages, Quechua: ''kúka'') is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant mainly recreational drug use, used recreationally for its euphoria, euphoric effects. It is primarily obtained from t ...

user who might falter in fulfilling the responsibilities of being governor. In losing the nominating contest to Richards, Mattox gained a reputation as a combative campaigner.

Pennsylvania special senatorial election, 1991

In 1991, Carville consulted for

Harris Wofford

Harris Llewellyn Wofford Jr. (April 9, 1926 – January 21, 2019) was an American attorney, civil rights activist, and Democratic Party politician who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1991 to 1995. A noted advocate of na ...

in his run for the open U.S. Senate seat left vacant when

Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

John Heinz

Henry John Heinz III (October 23, 1938 – April 4, 1991) was an American businessman and Republican politician from Pennsylvania. Heinz represented the Pittsburgh suburbs in the United States House of Representatives from 1971 to 1977 and ...

was killed in an April, 1991 plane crash. Following the crash, Carville, who was by then a close political confidant of

Governor Casey, hatched a plan to offer his appointment of the Senate seat to

Chrysler

Stellantis North America (officially FCA US and formerly Chrysler ()) is one of the " Big Three" automobile manufacturers in the United States, headquartered in Auburn Hills, Michigan. It is the American subsidiary of the multinational automoti ...

chairman

Lee Iacocca

Lido Anthony "Lee" Iacocca ( ; October 15, 1924 – July 2, 2019) was an American automobile executive best known for the development of the Ford Mustang, Continental Mark III, and Ford Pinto cars while at the Ford Motor Company in the 1960s, an ...

, an

Allentown Allentown may refer to several places in the United States and topics related to them:

*Allentown, California, now called Toadtown, California

*Allentown, Georgia, a town in Wilkinson County

*Allentown, Illinois, an unincorporated community in Taze ...

native who declined the offer within 24 hours. Attorney and later

Pittsburgh Steelers

The Pittsburgh Steelers are a professional American football team based in Pittsburgh. The Steelers compete in the National Football League (NFL) as a member club of the American Football Conference (AFC) North division. Founded in , the Steel ...

owner

Art Rooney II

Arthur Joseph Rooney II (born September 14, 1952) is the owner of the Pittsburgh Steelers of the National Football League (NFL).

Early life

Arthur Joseph Rooney II was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the eldest of nine children of Patricia (Re ...

was also considered, but Casey ultimately decided to appoint Wofford, then his state Secretary of Labor, to fill the seat, and Wofford faced a special election in November of that year.

Against the national backdrop of the first

Gulf War

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Iraq were carried out in two key phases: ...

, and a

dour economy, Wofford's general election opponent, George H.W. Bush's sitting

U.S. Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

,

Dick Thornburgh, was widely seen as a surrogate of the Bush political machine, and the contest was widely viewed as an early referendum on Bush's reelection prospects the following year.

Wofford was one of the first whites to graduate from

Howard University

Howard University (Howard) is a private, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is classified among "R2: Doctoral Universities – High research activity" and accredited by the Middle States Commissi ...

school of law, travelled to India and wrote a book on

Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, co-founded the

Peace Corps

The Peace Corps is an independent agency and program of the United States government that trains and deploys volunteers to provide international development assistance. It was established in March 1961 by an executive order of President John F. ...

, and was arrested at the

1968 Democratic National Convention

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was held August 26–29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Earlier that year incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection, thus making ...

for disorderly conduct, and was an opponent of apartheid. A philosophical progressive, and college president, he had served as an aide to both

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

, and a friend and adviser to

Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

Wofford had the air of an "anti-politician," rumpled in appearance, and uncomfortable with small talk who ran a campaign with themes of economic populism.

Though the issue polled a distant 5th in voter concerns, Wofford himself eschewed guidance from his consultants in demanding national health insurance be the centerpiece of his campaign. With the assistance of a guild of Philadelphia ophthalmologists, Wofford crafted an impactful slogan: "If criminals have access to a lawyer, working Americans should have a right to a doctor."

During the race, Carville helped Wofford craft an aggressive campaign,

with television advertisements attacking Thornburgh for taking expensive flights at public expense in government jets to junkets in places such as Hawaii. Another Wofford campaign commercial evoked an anti-establishmentarian air, linking Thornburgh to "the mess in Washington."

In the months leading into the election, Wofford overcame Thornburgh's 44 point lead in the polls and defeated him in November, garnering 1,860,760 votes (55 percent), to Thornburgh's 1,521,986 (45 percent).

Carville again consulted for Wofford's re-election campaign in 1994 when he was narrowly defeated by Republican

Rick Santorum

Richard John Santorum ( ; born May 10, 1958) is an American politician, attorney, and political commentator. A member of the Republican Party, he served as a United States Senator from Pennsylvania from 1995 to 2007 and was the Senate's thir ...

.

Los Angeles mayoral election, 1992–1993

In late 1992, and early 1993, Carville consulted for

San Fernando Valley

The San Fernando Valley, known locally as the Valley, is an urbanized valley in Los Angeles County, California. Located to the north of the Los Angeles Basin, it contains a large portion of the City of Los Angeles, as well as unincorporated ar ...

state assemblyman

Richard Katz in his run for the open 1993 Los Angeles mayoral election, which was the first time in 63 years that an incumbent mayor didn't appear on the ballot. Katz ran on a

tough-on-crime

In modern politics, law and order is the approach focusing on harsher enforcement and penalties as ways to reduce crime. Penalties for perpetrators of disorder may include longer terms of imprisonment, mandatory sentencing, three-strikes laws a ...

platform that included gun control, including new sales taxes on firearms and ammunition, and selling-off city-owned infrastructure, such as the

Ontario International Airport

Ontario International Airport is an international airport two miles east of downtown Ontario, California, Ontario, in San Bernardino County, California, United States, about east of downtown Los Angeles and west of downtown San Bernardino. It ...

, to pay police overtime, while promising not to raise property taxes. Despite retaining Carville, and spending a million dollars on campaign television commercials, Katz finished behind three other candidates, garnering 46,173 votes, or 9.73% of 474,366 total votes cast in the

nonpartisan blanket mayoral primary, and did not advance to the general election.

Bill Clinton's 1992 presidential campaign

In 1992, Carville helped lead

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

to a win against

George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushSince around 2000, he has been usually called George H. W. Bush, Bush Senior, Bush 41 or Bush the Elder to distinguish him from his eldest son, George W. Bush, who served as the 43rd president from 2001 to 2009; pr ...

in the presidential election. In crafting an economic strategy for Clinton, Carville reprised the

populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed ...

rhetoric his client, Pennsylvania Senator

Harris Wofford

Harris Llewellyn Wofford Jr. (April 9, 1926 – January 21, 2019) was an American attorney, civil rights activist, and Democratic Party politician who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1991 to 1995. A noted advocate of na ...

, successfully wielded the prior year, which was distilled into a series of articles

Donald L. Barlett

Donald L. Barlett (born July 17, 1936) is an American investigative journalist and author who often collaborates with James B. Steele. According to '' The Washington Journalism Review'', they were a better investigative reporting team than even ...

and

James B. Steele

James B. Steele (born January 3, 1943) is an American investigative journalist and author. With longtime collaborator Donald L. Barlett he has won two Pulitzer Prizes, two National Magazine Awards and five George Polk Awards during their thirty ...

wrote for ''

The Philadelphia Inquirer

''The Philadelphia Inquirer'' is a daily newspaper headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The newspaper's circulation is the largest in both the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the Delaware Valley metropolitan region of Southeastern Pennsy ...

''. The articles were re-printed into book form: ''America: What Went Wrong?'' which became a prop Clinton brandished effectively from the

stump

Stump may refer to:

* Stump (band), a band from Cork, Ireland and London, England

* Stump (cricket), one of three small wooden posts which the fielding team attempt to hit with the ball

*Stump (dog): Clussexx Three D Grinchy Glee (born 1998), 200 ...

during a time of

economic recession

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction when there is a general decline in economic activity. Recessions generally occur when there is a widespread drop in spending (an adverse demand shock). This may be triggered by various ...

. In bringing in the series of articles from the Wofford campaign, Carville imported an angry

left-wing populism

Left-wing populism, also called social populism, is a political ideology that combines left-wing politics with populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric often consists of anti-elitism, opposition to the Establishment, and speaking for the "comm ...

as a campaign theme.

One of the formulations he used in that campaign has entered common usage, derived from a list he posted in the campaign

war room

A command center (often called a war room) is any place that is used to provide centralized command for some purpose.

While frequently considered to be a military facility, these can be used in many other cases by governments or businesses. ...

to help focus himself and his staff, with these three points:

# Change vs. more of the same.

#

The economy, stupid.

# Don't forget health care.

Carville sought to shield Clinton from

Gennifer Flowers' allegations of her extramarital sexual affair which emerged shortly before the

1992 New Hampshire Democratic primary. Carville alleged that Flowers was paid $175,000 by a supermarket tabloid for sharing her story, and that "the mainstream media got sucker-punched" by her allegations. Carville set out to shame the press, berating reporters with charges of "cash for trash" journalism, and noted: "I'm a lot more expensive than Gennifer Flowers.". Flowers later brought a civil suit against Carville in 1999 (see below).

In June 1992, trailing

George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushSince around 2000, he has been usually called George H. W. Bush, Bush Senior, Bush 41 or Bush the Elder to distinguish him from his eldest son, George W. Bush, who served as the 43rd president from 2001 to 2009; pr ...

and

Ross Perot

Henry Ross Perot (; June 27, 1930 – July 9, 2019) was an American business magnate, billionaire, politician and philanthropist. He was the founder and chief executive officer of Electronic Data Systems and Perot Systems. He ran an inde ...

in the polls, Clinton limped toward the

national convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year National ...

, while the

Los Angeles riots crowded him out of news coverage. Carville knew he needed to bring Clinton back into the news limelight. He did so by orchestrating Clinton's splashy criticism of hip hop artist

Sister Souljah

Sister Souljah (born Lisa Williamson, the Bronx, New York, Bronx, New York) is an American author, activist, and film producer. Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party candidate Bill Clinton criticized her remarks about race in the U ...

in a prepared speech Clinton delivered at the

Rainbow Coalition's June 1992 "Rebuild America" conference in Washington, DC. Sister Souljah had remarked: "If black people kill black people every day, why not have a week and kill white people?" Clinton responded in his speech by saying, "If you took the words, 'white' and 'black' and you reversed them, you might think

David Duke

David Ernest Duke (born July 1, 1950) is an American white supremacist, antisemitic conspiracy theorist, far-right politician, convicted felon, and former Grand Wizard of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. From 1989 to 1992, he was a member ...

was giving that speech." Clinton refuted the suggestion that his speech was a calculated attempt to appeal to moderate and conservative swing voters by standing up to a core Democratic constituency.

had the effect of opening up a public war between Clinton and

Jesse Jackson

Jesse Louis Jackson (né Burns; born October 8, 1941) is an American political activist, Baptist minister, and politician. He was a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984 and 1988 and served as a shadow U.S. senator ...

.

In 1993, Carville was honored as Campaign District Manager of the Year by the

American Association of Political Consultants

The American Association of Political Consultants (AAPC) is the trade group for the political consulting profession in the United States. Founded in 1969, it is the world's largest organization of political consultants, public affairs professio ...

. His role in the Clinton campaign was documented in the feature-length Academy Award-nominated film ''

The War Room

''The War Room'' is a 1993 American documentary film about Bill Clinton's campaign for President of the United States during the 1992 United States presidential election. Directed by Chris Hegedus and D. A. Pennebaker, the film was released on D ...

''.

American politics during the 1990s

Carville continued to serve the

Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is the governing body of the United States Democratic Party. The committee coordinates strategy to support Democratic Party candidates throughout the country for local, state, and national office, as well a ...

in a political capacity during the 1990s, and had an ongoing need to regularly visit the White House to speak with then President Bill Clinton on political matters.

Accordingly, Carville was once one of only twenty individuals at the time who was granted a permanent "Non-Government Service" security badge, which were used for non-government employees, such as contractors, who needed regular access to the

White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

grounds. In consideration for the privilege of the permanent pass, the Clinton Administration asked Carville to submit to a full

security clearance

A security clearance is a status granted to individuals allowing them access to classified information (state or organizational secrets) or to restricted areas, after completion of a thorough background check. The term "security clearance" is ...

style

FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and its principal Federal law enforcement in the United States, federal law enforcement age ...

background check.

In response to the 1997 civil lawsuit then Arkansas state employee

Paula Jones

Paula Corbin Jones (born Paula Rosalee Corbin; September 17, 1966) is an American civil servant. A former Arkansas state employee, Jones sued United States President Bill Clinton for sexual harassment in 1994. In the initial lawsuit, Jones cite ...

filed against Bill Clinton over her claims of sexual harassment while attending a conference on official business, Carville infamously remarked: "Drag a hundred dollars through a trailer park and there's no telling what you'll find." South Carolina U.S. Senator

Lindsey Graham

Lindsey Olin Graham (born July 9, 1955) is an American lawyer and politician serving as the senior United States senator from South Carolina, a seat he has held since 2003. A member of the Republican Party, Graham chaired the Senate Committee ...

later made reference to Carville's trailer park line during the 2018

Brett Kavanaugh

Brett Michael Kavanaugh ( ; born February 12, 1965) is an American lawyer and jurist serving as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President Donald Trump on July 9, 2018, and has served since Oc ...

SCOTUS

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. Federal tribunals in the United States, federal court cases, and over Stat ...

confirmation hearings in reference to

Dr. Christine Blasey Ford. During an October, 2018 interview with Michael Smerconish on CNN, on the topic of Graham alluding to Carville's "drag $100", Carville remarked that, at the time, "I was making a joke", and added "I'm always complimented when people use my lines; you always like to leave a little legacy out there."

In 1999,

Gennifer Flowers

Gennifer Flowers (born January 24, 1950) is an American author, singer, model, actress, former State of Arkansas employee, and former TV journalist. In January 1998, President Bill Clinton testified under oath that he had a sexual encounter wit ...

, who had previously alleged an affair with Carville's 1992 client Bill Clinton, sued Carville and his colleague

George Stephanopoulos

George Robert Stephanopoulos ( el, Γεώργιος Στεφανόπουλος ; born February 10, 1961) is an American television host, political commentator, and former Democratic advisor. Stephanopoulos currently is a coanchor with Robin Robe ...

for

defamation

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

of character. In 2000, Flowers additionally named

Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, diplomat, and former lawyer who served as the 67th United States Secretary of State for President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, as a United States sen ...

as a defendant in the suit. Attorney

Larry Klayman of

Judicial Watch

Judicial Watch (JW) is an American conservative activist group that files Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) lawsuits to investigate claimed misconduct by government officials. Founded in 1994, JW has primarily targeted Democrats, in particu ...

, a conservative advocacy organization, represented her in the suit. Flowers contended that Carville and Stephanopoulos ignored obvious warning signs that news media reporting did not conclusively determine that tapes of her recorded telephone conversations with Clinton were "doctored."

In 2004, a federal district court dismissed the case with summary judgment.

Klayman then appealed the case on Flowers' behalf. In 2006, 14 years after the allegations of the affair became an issue for Bill Clinton's first presidential campaign, the

U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit (in case citations, 9th Cir.) is the U.S. federal court of appeals that has appellate jurisdiction over the U.S. district courts in the following federal judicial districts:

* District ...

affirmed the lower court's dismissal.

International elections 1990s to 2010s

Beginning in the mid-1990s, Carville worked on a number of election campaigns abroad, including those of

Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of th ...

, then

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern pr ...

, during the

2001 general election (in which Blair was comfortably re-elected), and with the

Liberal Party of Canada

The Liberal Party of Canada (french: Parti libéral du Canada, region=CA) is a federal political party in Canada. The party espouses the principles of liberalism,McCall, Christina; Stephen Clarkson"Liberal Party". ''The Canadian Encyclopedia'' ...

.

Carville viewed working campaigns abroad as more commercially lucrative, and with less reputational risk than campaigns in the United States noting in 2009: "If you help elect a president and then you get involved in a governor's race and you lose, it's going to be a little bit damaging to your reputation. But if you go to Peru and you run a presidential race and you lose, no one knows or cares. So why go to New Jersey and lose for 100 grand when you can go to Peru and lose for a million?"

Carville has been less forthcoming to the news media about his work abroad, and remarked to a

''Los Angeles Times'' reporter in 1999, "I won't comment on anything I do outside the U.S."

Work with U.S. State Department

In 2002, on behalf of the

U.S. State Department, Carville, and his wife, political consultant

Mary Matalin

Mary Joe Matalin (born August 19, 1953) is an American political consultant well known for her work with the Republican Party. She has served under President Ronald Reagan, was campaign director for George H. W. Bush, was an assistant to Presid ...

, met with a group of 55 Arab women political leaders during the

2002 United States midterm elections. The programming, "Women as Political Leaders" International Visitor (IV) Program", was the first program implemented under the auspices of the

Middle East Partnership Initiative

The U.S.-Middle East Partnership Initiative (MEPI) is a United States State Department program that fosters meaningful and effective partnerships between citizens, civil society, the private sector, and governments in the Middle East and North Afri ...

, a collection of 40 programs headed by then deputy assistant secretary for

Near East Affairs Liz Cheney

Elizabeth Lynne Cheney (; born July 28, 1966) is an American attorney and politician who has been the U.S. representative for since 2017, with her term expiring in January 2023. She chaired the House Republican Conference, the third-highest p ...

. In addition to events with Carville and Matalin, the group met with congressional, state and local campaign staff, and observed campaign work during their visits to

Concord, New Hampshire

Concord () is the capital city of the U.S. state of New Hampshire and the seat of Merrimack County. As of the 2020 census the population was 43,976, making it the third largest city in New Hampshire behind Manchester and Nashua.

The village of ...

,

Dallas, Texas

Dallas () is the third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 million people. It is the largest city in and seat of Dallas County w ...

,

Detroit, Michigan

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at ...

,

Toledo, Ohio

Toledo ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Lucas County, Ohio, United States. A major Midwestern United States port city, Toledo is the fourth-most populous city in the state of Ohio, after Columbus, Cleveland, and Cincinnati, and according ...

,

Raleigh, North Carolina

Raleigh (; ) is the capital city of the state of North Carolina and the List of North Carolina county seats, seat of Wake County, North Carolina, Wake County in the United States. It is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, second-most ...

, and

Tallahassee

Tallahassee ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Florida. It is the county seat and only incorporated municipality in Leon County. Tallahassee became the capital of Florida, then the Florida Territory, in 1824. In 2020, the population ...

and

Tampa, Florida

Tampa () is a city on the Gulf Coast of the United States, Gulf Coast of the U.S. state of Florida. The city's borders include the north shore of Tampa Bay and the east shore of Old Tampa Bay. Tampa is the largest city in the Tampa Bay area and ...

.

That year, Carville also proposed visiting Arab and Muslim nations on behalf of the US government to do "some kind of propaganda," adding "I'd love to use my experience and skills to tell people about my country and what's available to them beyond hopelessness and terrorism." He added, "What the terrorists are after is the younger and increasingly poor population. What they are offering is not that much, but we are not doing a good job telling those young people the other side of the story. It's time we told them about choices they have without imposing American values."

Greece, 1993

Carville, Begala, and Mary Matalin advised incumbent Greek Prime Minister

Konstantinos Mitsotakis

Konstantinos Mitsotakis ( el, Κωνσταντίνος Μητσοτάκης, ; – 29 May 2017) was a Greek politician who was 7th Prime Minister of Greece from 1990 to 1993. He graduated in law and economics from the University of Athens. Hi ...

in an election that saw local Greek press allege United States interference in the election. Unpopular because his program of economic austerity and privatization, Mitsotakis failed in his reelection bid, and lost to democratic socialist

Andreas Papandreou

Andreas Georgiou Papandreou ( el, Ανδρέας Γεωργίου Παπανδρέου, ; 5 February 1919 – 23 June 1996) was a Greek economist, politician and a dominant figure in Greek politics, known for founding the political party PASOK, ...

.

Brazil, 1994

In 1994, Carville consulted for

Fernando Henrique Cardoso

Fernando Henrique Cardoso (; born 18 June 1931), also known by his initials FHC (), is a Brazilian sociologist, professor and politician who served as the 34th president of Brazil from 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2002. He was the first Brazi ...

in his successful 1994 campaign for the Brazilian presidency. Cardoso, a professor and

Fulbright Fellow

The Fulbright Program, including the Fulbright–Hays Program, is one of several United States Cultural Exchange Programs with the goal of improving intercultural relations, cultural diplomacy, and intercultural competence between the people of ...

lectured in the United States during the 1980s at

Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

on issues of democracy in Brazil. Cardoso, often nicknamed "FHC", was elected with the support of a heterodox alliance of his own Social Democratic Party, the PSDB, and two right-wing parties, the

Liberal Front Party

The Democrats ( pt, Democratas, DEM) was a centre-right political party in Brazil that merged with the Social Liberal Party to found the Brazil Union in 2021. It was founded in 1985 under the name of Liberal Front Party (''Partido da Frente Libe ...

(PFL) and the

Brazilian Labour Party (PTB). During his tenure in office, Cardoso's administration liquidated public assets and deepened the

privatization

Privatization (also privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation when ...

of government-owned enterprises in steel milling, telecommunications and mining, along with making reforms to Brazil's social security income program and tax systems.

Honduras, 1997

In 1997, Carville consulted for then leader of the

National Congress of Honduras,

Carlos Flores Facussé

Carlos Roberto Flores Facussé (born 10 March 1950) is a Honduran politician and businessman who served as the President of Honduras from 1998 to 2002. A member of the Liberal Party, Flores was previously the President of the National Congr ...

in his

presidential campaign.

Flores attended the

American School of Tegucigalpa, studied international finance at

Louisiana State University

Louisiana State University (officially Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, commonly referred to as LSU) is a public land-grant research university in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The university was founded in 1860 nea ...

in the early 1970s, and married a U.S. citizen from Tennessee.

He later became the publisher of his family's ''

La Tribuna'', a leading Honduran newspaper, and served on various corporate boards of directors, including the

Central Bank of Honduras, and became involved in politics. Flores was aligned with former president

Roberto Suazo Cordova's ''Rodista'' faction, the more conservative wing of the

liberal party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

. Vowing to move Honduras past its image of being primarily a banana and coffee exporter, Flores campaigned on his "New Agenda" platform, that included a ten point plan to stabilize the economy. Flores distanced himself from the outgoing

Reina administration, while successfully portraying himself as an opposition candidate from the same party.

In the November, 1997 general election, Flores faced

National party candidate

Nora Gúnera de Melgar

Alba Nora Gúnera Osorio (May 1942 – 1 October 2021) was a Honduran politician and wife of General Juan Alberto Melgar, the Honduran military Head of State from 1975 to 1978. After being elected mayor of Tegucigalpa, she ran for presidency for ...

, the wife of General

Juan Alberto Melgar Castro

Juan Alberto Melgar Castro (20 June 1930 – 2 December 1987) was a army officer in the Honduran military who served as the head of state of Honduras from 22 April 1975 to 7 August 1978, when he was removed from power by others in the military ...

, who seized power in a

1975 coup which removed then president

Oswaldo López Arellano

Oswaldo Enrique López Arellano (30 June 1921 – 16 May 2010) was a Honduran politician who twice served as the President of Honduras, first from 1963 to 1971 and again from 1972 until 1975.

Early life

Lopez was born in Danlí to Enrique L� ...

after his

bananagate

The Union of Banana Exporting Countries ( es, Unión de Países Exportadores de Banano or UPEB) was a cartel of Central and South American banana exporting countries established in 1974, inspired by OPEC. Its aim was to achieve better remuneration ...

bribery scandal with

United Fruit Company

The United Fruit Company (now Chiquita) was an American multinational corporation that traded in tropical fruit (primarily bananas) grown on Latin American plantations and sold in the United States and Europe. The company was formed in 1899 fro ...

.

Flores defeated his opponent by a 10% margin of 195,418 votes out of a total of 1,885,388 votes cast. Gúnera de Melgar's campaign was aided by the assistance

Dick Morris

Richard Samuel Morris (born November 28, 1948) is an American political author and commentator who previously worked as a pollster, political campaign consultant, and general political consultant.

A friend and advisor to Bill Clinton during ...

, rival political consultant and also a political adviser to

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

. Morris claimed he had no knowledge of Carville's involvement with his opponent until after the election.

In October, 1998,

Hurricane Mitch

Hurricane Mitch is the second-deadliest Atlantic hurricane on record, causing over 11,000 fatalities in Central America in 1998, including approximately 7,000 in Honduras and 3,800 in Nicaragua due to cataclysmic flooding from the slow motion ...

devastated Honduras, and post hurricane reconstruction efforts resulted in

international development banks renegotiating much of Honduras'

external debt

A country's gross external debt (or foreign debt) is the liabilities that are owed to nonresidents by residents. The debtors can be governments, corporations or citizens. External debt may be denominated in domestic or foreign currency. It incl ...

in exchange for

structural adjustment policies. After selling state-owned airports and energy companies, Flores unsuccessfully attempted to privatize

Hondutel

Hondutel (Empresa Hondureña de Telecomunicaciones), is the Honduras government's telecommunications company.

It has a monopoly on international calls.

History

Creation

The organization was created on May 7, 1976, as an autonomous organizat ...

, the state-owned telephone utility, and when that effort failed, the

International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution, headquartered in Washington, D.C., consisting of 190 countries. Its stated mission is "working to foster globa ...

froze the distribution of loans and demanded that the government further accelerate its

privatization

Privatization (also privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation when ...

programs.

Ecuador, 1998

In 1998, Carville help craft a successful strategy to elect

Jamil Mahuad Witt as President of Ecuador. Mahuad, an Ecuadorian-born attorney, earned a

Master of Public Administration

The Master of Public Administration (M.P.Adm., M.P.A., or MPA) is a specialized higher professional post graduate degree in public administration, similar/ equivalent to the Master of Business Administration but with an emphasis on the issues of ...

from

Harvard Kennedy School

The Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), officially the John F. Kennedy School of Government, is the school of public policy and government of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The school offers master's degrees in public policy, public ...

, where he was Mason Fellow. He was also a

US State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other nati ...

-sponsored

Fulbright Fellow

The Fulbright Program, including the Fulbright–Hays Program, is one of several United States Cultural Exchange Programs with the goal of improving intercultural relations, cultural diplomacy, and intercultural competence between the people of ...

, who lectured in ethics and politics at several universities.

Mahuad was elected Mayor of

Quito

Quito (; qu, Kitu), formally San Francisco de Quito, is the capital and largest city of Ecuador, with an estimated population of 2.8 million in its urban area. It is also the capital of the province of Pichincha. Quito is located in a valley o ...

in the 1990s before retaining the services of Carville to help him win the Ecuadorian presidency, in a campaign in which Mahuad touted his educational background at Harvard Kennendy School.

In the wake of an economic crisis from falling oil prices and stagnant economic growth, Mahuad decreed a state of emergency, and embarked on

austerity

Austerity is a set of political-economic policies that aim to reduce government budget deficits through spending cuts, tax increases, or a combination of both. There are three primary types of austerity measures: higher taxes to fund spend ...

measures to stifle rampant inflation, including

sales tax

A sales tax is a tax paid to a governing body for the sales of certain goods and services. Usually laws allow the seller to collect funds for the tax from the consumer at the point of purchase. When a tax on goods or services is paid to a govern ...

and gasoline tax increases, freezing bank account withdrawals, and the

dollarization

Currency substitution is the use of a foreign currency in parallel to or instead of a domestic currency. The process is also known as dollarization or euroization when the foreign currency is the dollar or the euro, respectively.

Currency subs ...

of the economy which included the sudden voiding and invalidation of the

Sucre

Sucre () is the Capital city, capital of Bolivia, the capital of the Chuquisaca Department and the List of cities in Bolivia, 6th most populated city in Bolivia. Located in the south-central part of the country, Sucre lies at an elevation of . T ...

, Ecuador's currency since 1884. In January 2000, Mahuad was forced from office in a military coup following demonstrations by Ecuadorians. Mahuad fled to exile in the United States. In 2014, an Ecuadorian court convicted Mahuad, in absentia, of embezzlement during his time in office, and sentenced him to twelve years in prison.

Interpol

The International Criminal Police Organization (ICPO; french: link=no, Organisation internationale de police criminelle), commonly known as Interpol ( , ), is an international organization that facilitates worldwide police cooperation and cri ...

also issued a warrant for his arrest.

Panama, 1998

In 1998, the

Democratic Revolutionary Party

The Democratic Revolutionary Party ( es, Partido Revolucionario Democrático, PRD) is a political party in Panama founded in 1979 by General Omar Torrijos. It is generally described as being positioned on the centre-left.

History

Since its creat ...

(PRD) party in Panama retained Carville as their main adviser to help re-elect then

term-limited

A term limit is a legal restriction that limits the number of terms an officeholder may serve in a particular elected office. When term limits are found in presidential and semi-presidential systems they act as a method of curbing the potenti ...

President

Ernesto Pérez Balladares

Ernesto Pérez Balladares González-Revilla (born June 29, 1946), nicknamed ''El Toro'' ("The Bull"), is a Panamanian politician who was the President of Panama between 1994 and 1999.

Educated in the United States, Pérez Balladares worked as ...

during an election where opposition figures suggested that Perez Balladares was hoping to convey the impression that the Clinton Administration in the United States secretly favored a second term for him. Pérez Balladares, who attended college in the United States at the

University of Notre Dame

The University of Notre Dame du Lac, known simply as Notre Dame ( ) or ND, is a private Catholic research university in Notre Dame, Indiana, outside the city of South Bend. French priest Edward Sorin founded the school in 1842. The main campu ...

before attaining his Master's at the

Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania

The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania ( ; also known as Wharton Business School, the Wharton School, Penn Wharton, and Wharton) is the business school of the University of Pennsylvania, a Private university, private Ivy League rese ...

, reformed Panama's Labor Code,

privatized

Privatization (also privatisation in British English) can mean several different things, most commonly referring to moving something from the public sector into the private sector. It is also sometimes used as a synonym for deregulation when ...

Panama's telephone and electrical utilities, and ushered Panama into the

World Trade Organization

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is an intergovernmental organization that regulates and facilitates international trade. With effective cooperation

in the United Nations System, governments use the organization to establish, revise, and e ...

during his tenure. Despite massive spending by the PRD, including the hiring of Carville to craft an effective political strategy, the proposal to lift his term limitation was defeated by a margin of almost 2 to 1.

Israel, 1998–1999

At the suggestion of

President Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and again ...

, who had grown frustrated with

Benjamin Netanyahu

Benjamin "Bibi" Netanyahu (; ; born 21 October 1949) is an Israeli politician who served as the ninth prime minister of Israel from 1996 to 1999 and again from 2009 to 2021. He is currently serving as Leader of the Opposition and Chairman of ...

's intransigence in the peace process, Carville, along with colleagues

Bob Shrum

Robert M. "Bob" Shrum (born July 21, 1943) is the Director of the Center for the Political Future and the Carmen H. and Louis Warschaw Chair in Practical Politics at the University of Southern California, where he is a Professor of the Practice o ...

, a speechwriter for President Clinton, and

Stanley Greenberg, consulted in late 1998 and early 1999 for

Labor Party candidate

Ehud Barak

Ehud Barak ( he-a, אֵהוּד בָּרָק, Ehud_barak.ogg, link=yes, born Ehud Brog; 12 February 1942) is an Israeli general and politician who served as the tenth prime minister from 1999 to 2001. He was leader of the Labor Party until Jan ...

to help him prepare for the 1999 prime ministerial election.

Carville and colleagues endeavored to help Barak seize control of the daily debate, and boost his struggling challenge to incumbent head-of-state

Binyamin Netanyahu. Short declarative sentences, sound bites, rapid response, repetition, wedge issues, ethnic exploitation, nightly polling, negative research, searing attack advertisements on television, all familiar tools of American politics, arrived on the Israeli political scene during the election, as a part of what Netanyahu's director of communications, David Bar-Illan characterized as an Americanization of the election, and Netanyahu advisers implying White House meddling in an Israeli election. Barak won election by a double digit margin and served for over two years, before calling a special prime ministerial election in 2001.

Argentina, 1999

Carville consulted for

Buenos Aires Province

Buenos Aires (), officially the Buenos Aires Province (''Provincia de Buenos Aires'' ), is the largest and most populous Argentine province. It takes its name from the city of Buenos Aires, the capital of the country, which used to be part of th ...

Governor

Eduardo Duhalde

Eduardo Alberto Duhalde (; born 5 October 1941) is an Argentine Peronist politician who served as the interim President of Argentina from January 2002 to May 2003. He also served as Vice President and Governor of Buenos Aires in the 1990s.

Bor ...

in his 1999 run for president of Argentina as the

Justicialist Party

The Justicialist Party ( es, Partido Justicialista, ; abbr. PJ) is a major political party in Argentina, and the largest branch within Peronism.

Current president Alberto Fernández belongs to the Justicialist Party (and has, since 2021, served ...

nominee. Carville remarked in May, 1999 that U.S. Ambassador to Argentina

James Cheek introduced him to Duhalde in January, 1998. Carville's consulting fee ran $30,000 per month, in 1999 US dollars, added to a percentage of campaign advertisements, plus first class airfare and hotel expenses.

Duhalde spent much of the campaign embroiled in a power struggle with his own party and incumbent President

Carlos Menem

Carlos Saúl Menem (2 July 1930 – 14 February 2021) was an Argentine lawyer and politician who served as the President of Argentina from 1989 to 1999. Ideologically, he identified as a Peronist and supported economically liberal policies. H ...

who was barely dissuaded from running for a third term despite

constitutional

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...